A Senate committee voted down a bill that would have required local government approval of carbon capture and sequestration projects, calling it an “extra level of bureaucracy.”

Members of the Senate Committee on Environmental Affairs voted down the passage of Senate Bill 247, which would have required the approval of counties, cities or towns in order to move forward on carbon capture and sequestration projects, in a 4 to 7 vote.

The bill was supported in committee by the Association of Indiana Counties, which said local input was needed to gauge support for a potential project carbon dioxide storage project in Benton County.

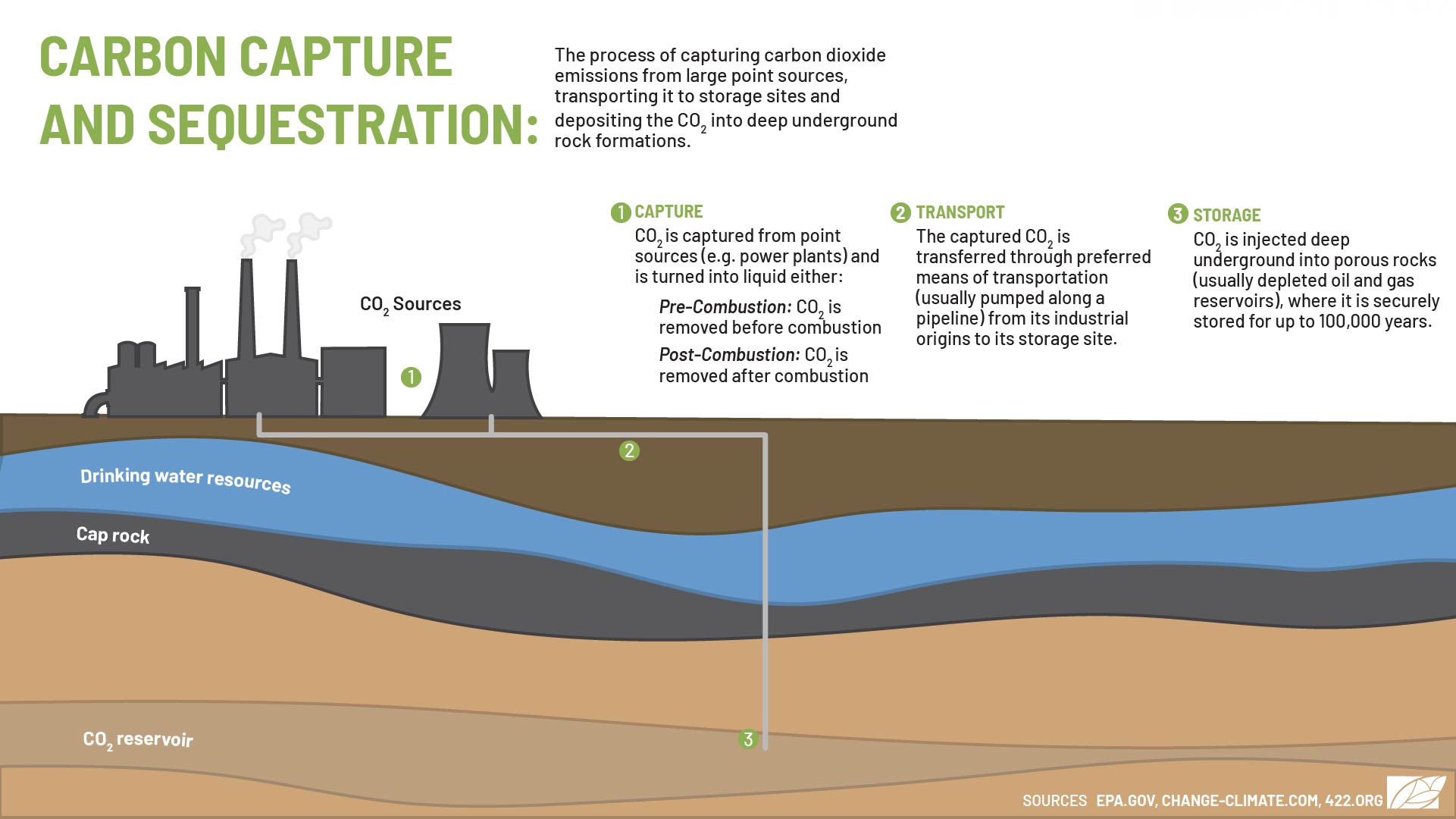

Carbon capture and sequestration projects essentially consist of three parts. First is carbon capture, in which carbon dioxide emitted from facilities is captured before entering the atmosphere. Next, the collected carbon dioxide is turned into a part-gas, part-liquid substance called a supercritical fluid. Finally, the supercritical carbon dioxide is injected deep underground.

Carbon capture and sequestration often do not happen at the same place and require pipelines to transport the carbon dioxide to wherever it will be sequestered, usually depleted oil and gas reservoirs, deep saline reservoirs and coal seams that cannot be mined.

About a dozen commercial carbon capture facilities currently exist in the U.S., but only two sequester carbon deep underground — the Archer Daniels Midland Co. Illinois Industrial CCS Project in Decatur, Illinois and the Red Trail Energy LLC CCS Project in Richardton, North Dakota.

Several companies are trying to establish CCS projects in Indiana. Wabash Valley Resources LLC is attempting to set up an Indiana General Assembly-backed CCS pilot project in Vigo County. Canadian developers Vault 44.01 Inc. and Indiana-based ethanol producer Cardinal Ethanol LLC are trying to launch a project in Randolph County as One Carbon Partnership LLC. Cleveland-Cliffs Inc. is pursuing funding for a CCS project at its Burns Harbor steel mill.

BP has begun looking at Benton County as a possible home for a CCS project that would store carbon dioxide from its Whiting Refinery in Lake County.

SB 247 sponsor Sen. Rick Niemeyer, who is also chair of the Senate Committee on Environmental Affairs, said the bill would modify a nearly year-old law allowing CCS projects in the state to permit local governments to have a say in projects planned in their jurisdiction.

Niemeyer said SB 247 was drafted as a direct result of BP’s interest in Benton County.

“The company came in and did some work there, some soil testing and seismic testing, and it really was an uproar a little bit in Benton County because people didn't know what was going on. There was not a lot of outreach before that happened,” Niemeyer said during the Feb. 20 hearing. “Nobody knew what the project was and how it was going to work. How far was the bloom gonna go on underneath the ground? How far was it gonna go with this carbon? Those questions needed to be answered, and this will help do it.”

House Enrolled Act 1209, passed in 2022, allows CCS projects to go ahead as long as they have the proper federal permits, have made a “good faith effort” to obtain the consent of all pore space owners where the carbon will be sequestered and have obtained the consent of at least 70% of landowners on the surface area above the proposed storage facility.

SB 247 sought to require all CCS projects to receive an ordinance approving the project from the local government where the carbon would be sequestered and where the communities through which the carbon transmission pipelines would be built. The bill was later amended to remove the pipeline portion of the bill.

SB 247 was opposed by the Northwest Indiana Forum, the Indiana Chamber of Commerce and trade organizations for manufacturers and the oil and gas industry, which argued that the legislation would add an layer of bureaucracy that would allow counties to block projects like some counties block utility scale wind and solar energy projects.

Carbon sequestration projects are required to obtain a Class VI Underground Injection Control permit from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency in order to store carbon dioxide underground. The EPA has only ever issued two Class VI permits, which have taken about six years to complete, on average.

The EPA has supported giving states the power to run their own Class VI permitting program, but the Indiana Department of Natural Resources, which oversees the state’s oil, gas and water well permits, said it did not intend to pursue that opportunity “at this time.”

Beyond the EPA, bill opponents said companies looking to establish CCS projects must get permits and follow other regulations from the US Department of Transportation, the Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration, DNR, Indiana Department of Environmental Management and the Indiana Utility Regulatory Commission for various parts of the project.

The permitting process is lengthy due to several potential points of failure, including pipeline leaks, carbon dioxide leakage and the potential increased occurrence of earthquakes.

A 2022 Pipeline Safety Trust report found the Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration regulates carbon dioxide only when it is compressed to a supercritical state with a concentration of 90% or higher. The transport of carbon dioxide in any other state or concentration is entirely unregulated.

Leaks of sequestered carbon dioxide could take decades to find and could cause significant damage to people and the environment, according to specialty insurance broker Amwins.

Bill opponents said regulatory slowdowns could impede companies in Indiana from receiving a share of billions of dollars allocated by the US Department of Energy for CCS and hydrogen hub projects.

The DoE will award $7 billion to six to 10 regional hubs that will produce hydrogen in hopes the gas will eventually replace natural gas, which is made up almost entirely of the potent greenhouse gas methane.

Indiana Gov. Eric Holcomb has signed a memorandum of understanding joining Indiana to a regional hydrogen hub along with Illinois, Kentucky, Michigan, Minnesota, Ohio and Wisconsin with an aim to receive part of the funding.

The Energy Department will also award $3.5 billion to fund carbon capture and sequestration pilot projects and demonstration projects.

Some hydrogen production methods using fossil fuels involve sequestering excess carbon dioxide underground, and the DoE is requiring hydrogen hubs to include infrastructure for carbon capture and sequestration for the funding.

Bill opponents said the extra layer of approval negatively affects the state’s eligibility for the funding.

“The competition is fierce for this project. Fierce. Indiana, as I understand it, has made the first cut, has made the second cut and has moved up in the application process. But now, to proceed, Indiana has joined in with other states around us to continue to move forward,” said American Petroleum Institute representative Maureen Ferguson. “I would argue that this extra layer of an additional county approval, again, just throws the black mark on Indiana's ability and willingness to be eligible for this application.”

It’s unclear how much of the money would benefit Hoosiers.

Some studies project more than 4,500 new project jobs and 3,360 permanent jobs could be created if the state fully backs CCS projects.

DoE-funded CCS projects have a history of existing only long enough for a company to reap financial benefits before shutting down.

A US Government Accountability Office report found that between 2009 and 2021, the DoE invested $1.1 billion in CCS demonstration projects. Only three were built, including the Archer Daniels Midland Co. Illinois Industrial CCS Project in Decatur, Illinois; the Air Products and Chemicals Inc. Industrial Carbon Capture and Storage program in Port Arthur, Texas; and the NRG Energy Inc. Petra Nova project in Richmond, Texas.

Only the Illinois Industrial CCS Project still sequesters carbon dioxide. The Petra Nova project shut down in 2020 due to high energy costs, and the Industrial Carbon Capture and Storage program transitioned to enhanced oil recovery, the process of using captured carbon to help extract difficult-to-reach oil or natural gas.