After years of limited action, the federal government is moving forward with multiple plans to establish regulations limiting toxic contamination from two PFAS chemicals used for nearly a century to make products resistant to heat, water, grease and stains.

But the proposed rules could leave many understudied and potentially toxic PFAS chemicals at large in Hoosier air and waterways.

Scientists at Indiana’s research universities are working to fill in data gaps on PFAS chemicals, undertaking multidisciplinary studies to better understand how PFAS chemicals spread and affect Hoosier health.

PFAS HEALTH RISK

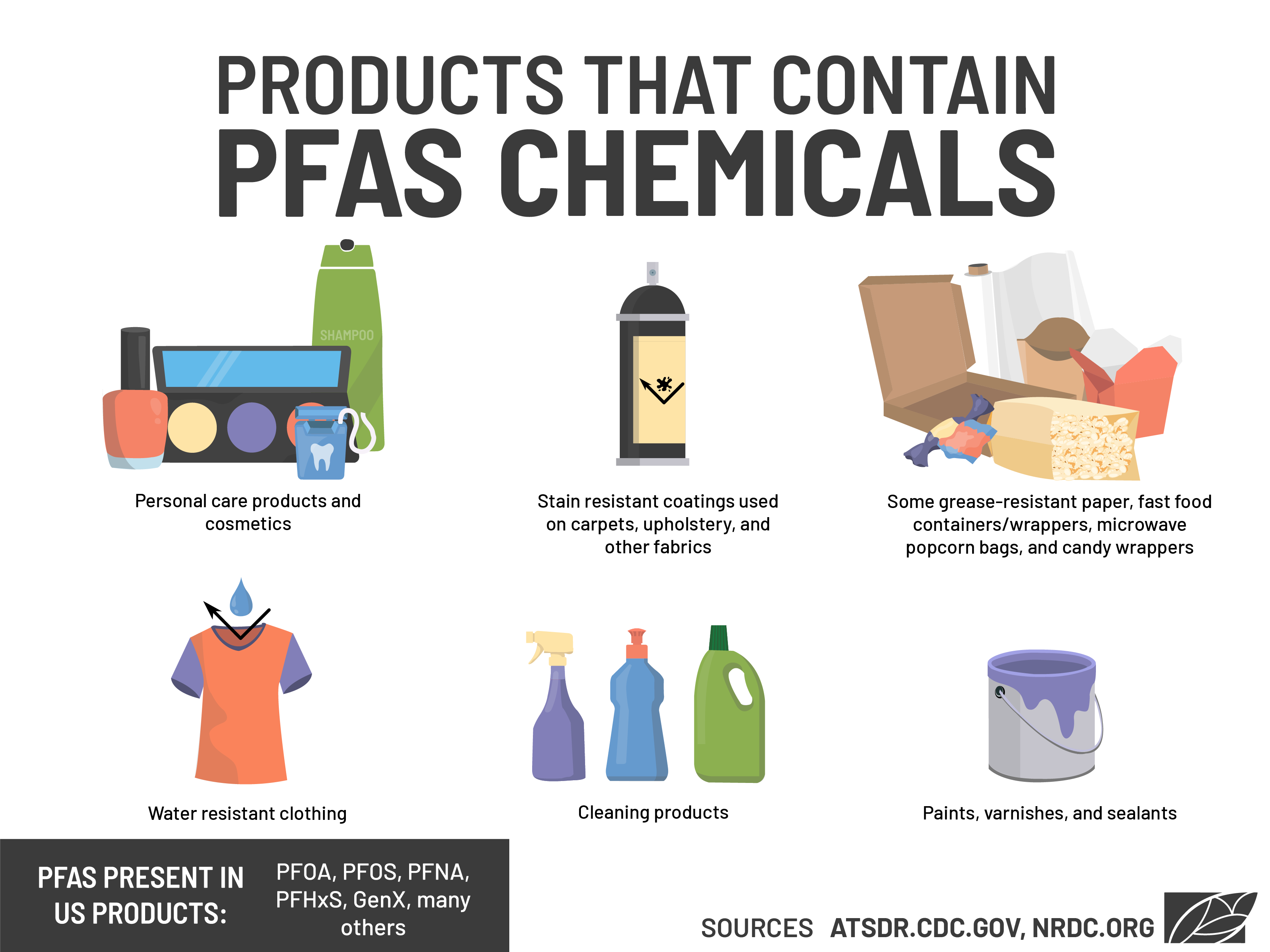

PFAS chemicals have been used since the 1940s to make products widely known by their brand names, like Teflon, Gore-Tex and Scotchgard.

The chemicals have been linked to a series of health effects, like an increased risk of developing kidney or testicular cancer, damage to the liver and immune system, increased cholesterol levels, increased risk of high blood pressure or pre-eclampsia in pregnant women and decreased vaccine response in children.

“They're detecting them everywhere in the environment,” said Jennifer Freeman, professor of toxicology at Purdue University’s School of Health Sciences. “Almost every human has them in their blood, and they're everywhere around the globe that you can detect them.”

PFAS are known as “forever chemicals” due to their extreme persistence — their ability to remain in the environment without breaking down for more than a thousand years. That persistence has allowed them to travel throughout every corner of the globe.

The chemicals have been found in many places in the environment, from Indiana tap water to Antarctic rainfall. The chemicals have been detected in the blood of most Americans at levels many times higher than those found in many other countries, potentially due to the long history of PFAS manufacturing and use.

FEDERAL PFAS MOVES

The Biden administration is moving forward with multiple proposal to regulate PFOA and PFOS — two types of PFAS chemicals — through U.S. Environmental Protection Agency rules.

The EPA is pursuing a limit on the amount of PFOA and PFOS chemicals that can be found in treated drinking water and expects to develop a proposed National Drinking Water Regulation for the two chemicals by the end of 2022.

The agency is also in the early stages of pursuing a hazardous chemical designation for the two under the nation’s Superfund law. That designation would require facilities to report PFOA and PFOS releases, including those that have happened historically, and would make those facilities responsible for their cleanup.

The proposals are part of the agency’s PFAS Strategic Roadmap, a three-year plan to pursue other actions to assess the extent of PFAS contamination in the U.S.

But the EPA’s planned enforceable regulations are focused almost solely on PFOA and PFOS due to their link to a wide array of health risks found during decades of studies.

TWO OF THOUSANDS

The 3M Co. created PFOA and PFOS in the 1950s. The company undertook various private studies on the toxicity of the chemicals that it kept to itself until it turned some over to the EPA in 2000. Others were released due to lawsuits filed against the company.

The health effects of PFOA on humans were studied extensively as a result of the settlement of a class action lawsuit launched by 80,000 private citizens against E.I. du Pont de Nemours & Co. and its offshoot company, Chemours Co., for its use of PFOA in the production of Teflon coatings.

The resulting C8 Health Project studied 69,030 people over a 13-month period between 2005 and 2006, collecting demographic data, medical diagnoses, laboratory testing and PFAS concentrations.

The U.S. Department of Defense has studied PFOA and PFOS since the early 1970s. The chemicals were an ingredient in early versions of the military’s firefighting foam, known as aqueous film-forming foam.

Studies from various military branches in the 1970s found PFOA, PFOS and other PFAS chemicals were toxic to the environment and animal life. Subsequent research in the 1980s found PFAS chemicals in the firefighting foam were toxic to mice and marine organisms.

About 700 current and former military installations around the country, including more than a dozen in Indiana, are being investigated for the release of aqueous film-forming foam and PFAS contamination.

The combination of public and private research gave scientists a greater understanding of the effects of PFOA and PFOS, but American companies have mostly moved on from those chemicals and adopted replacement PFAS for which there is much less toxicity data.

NEWER CHEMICALS

The EPA recently expanded its knowledge of PFAS toxicity by finalizing toxicity assessments for two additional successor PFAS chemicals, GenX and PFBS.

“GenX chemicals” are what the EPA calls hexafluoropropylene oxide dimer acid and hexafluoropropylene oxide dimer acid ammonium salt, two chemicals created by DuPont to replace PFOA in Teflon and other products. GenX chemicals and some other lawsuit-magnet chemicals are now owned by DuPont spinoff, the Chemours Co.

The company argues GenX chemicals are safe for its intended use — the manufacturing of high-performance fluoropolymers, a family of plastic resins used to make products resistant to high heat and corrosive elements.

“There is over a decade of scientific data about HFPO-Dimer Acid that confirm its safety profile. Multiple studies demonstrate that it does not bioaccumulate and, if incidental exposure were to occur, it’s rapidly eliminated from the body,” Chemours wrote on its GenX page.

Despite the company’s public position, DuPont data submitted to the EPA and later obtained by The Intercept points to potential toxicity to humans. The data indicated the chemicals damaged the liver and kidney, caused developmental effects, suppressed the immune system and led to the development of cancerous liver and pancreas tumors in lab animals.

The EPA’s assessment, which was limited to oral exposure to GenX chemicals due to a lack of research, included DuPont’s findings.

PFBS was created in the late 1990s by 3M to replace PFOS. The company began creating surfactants, the compounds that change the way water molecules react to other molecular surfaces, based on PFBS in 2002 and released accompanying data in a technical bulletin that led the company to declare PFBS a “sustainable alternative” to PFOS-based products.

PFBS is mainly used in firefighting foams and during chrome electroplating as a mist suppressant. The chemical is also found in some food packaging products

The company admitted the persistence of PFBS, but downplayed its significance.

“PFBS is persistent, but persistence in and of itself is not a concern if a material is practically non-toxic and does not bioconcentrate,” the company wrote in its environmental, health, safety and regulatory profile for PFBS.

The EPA’s 2021 PFBS assessment linked the chemical to health problems affecting the thyroid, reproductive organs, fetal development and kidney function in animals. Due to a lack of research into the chemical, only asthma and cholesterol studies have found statistically positive associations with PFBS exposure in humans despite evidence pointing to a likelihood of more adverse health links.

The assessment warned that more research was necessary to ascertain whether PFBS is harmful to humans because too few studies have been done on the chemical’s effects. The assessment found that no studies have been done to evaluate the association between PFBS and potential cancer outcomes.

The EPA updated existing non-enforceable guidelines called drinking water lifetime health advisories for PFOA and PFOS this summer and established advisories for PFBS and GenX due to “newly available science.”

FILLING IN DATA GAPS

The Biden administration is moving forward with regulation for the most pervasive PFAS substances, but many PFAS chemicals currently being used in the U.S. will go unregulated despite having similar chemical structures.

The EPA’s Master List of PFAS Substances, a collection of all the lists of PFAS chemicals the EPA can find, including some that liberally list partially fluorinated substances, polymers and other PFAS-related reaction products, lists 12,034 existing PFAS chemicals.

But even a strict definition would include thousands of chemicals.

“It's a humongous group of chemicals,” Freeman said. “We know so much about two of over 4,000 of them. And from a toxicologist point of view, we know that there's similar chemical structures. But we also know that we just can't assume they're all going to have the same sort of toxicity effects.”

Freeman and her colleagues at Purdue University are working to increase the amount of existing data that shows how PFAS chemicals affect humans and the environment.

The researchers are studying PFAS chemicals through different disciplines, learning how the chemicals affect humans and wildlife directly, how the chemicals can spread, how to replace the chemicals and how to destroy the chemicals.

Freeman is researching the neurotoxicity of some PFAS chemicals on humans by looking at how the chemicals affect zebrafish.

Zebrafish, the striped freshwater fish related to minnows, have been used in scientific research for over a century. They are particularly useful for finding how chemicals or diseases can affect humans because zebrafish have similar amounts of body parts and about 70% of the genes found in humans.

“We're trying to look at impacts on the brain. And we know that you have a blood-brain barrier that helps to block out a lot of chemicals from getting in, but the smaller chemicals with shorter chemical structures actually get into the brain easier,” Freeman said. “So that’s part of the questions that we’ve been asking as we’re getting these replacement PFAS put in. They’re actually shorter carbon chains compared to the longer ones that we’ve been phasing out. Will they be able to get into the brain easier and cause more neurotoxicity or different types of neurotoxicity than we see with some of the older generational chemicals?”

Freeman and associate professor of chemical engineering Chongli Yuan examined the impact of low-dose PFOA and GenX exposure on neurons that control movement, behavioral processes and other brain functions.

Freeman’s colleague, associate professor of toxicology Jason Cannon, has researched how PFAS exposure is linked to chronic and age-related psychiatric illnesses and neurodegenerative diseases, like attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children and Parkinson’s disease and Alzheimer’s disease in elderly populations.

Professors Jason Hoverman and Marisol Sepulveda, from Purdue’s Department of Forestry and Natural Resources, and professor Linda Lee of Purdue’s Department of Environmental and Ecological Engineering has studied PFAS removal in drinking water and how microbial growth in point-of-use systems affects PFAS removal efficiencies.

Carlos Martinez, associate professor of material engineering, is working on developing a PFAS-free foam formulation. Assistant professor of health sciences Aaron Specht has developed non-invasive and non-destructive techniques to measure PFAS using x-ray fluorescence.

University of Notre Dame researchers, like professor of chemistry and biochemistry Graham Peaslee, have found PFAS chemicals in fast food packaging, firefighter turnout gear and cosmetics.

At Indiana University, researchers like associate research scientist Amina Salamova and assistant professor Marta Venier have studied the presence of PFAS chemical in private wells, in breast milk, cosmetics and in remote Arctic communities.

Freeman said the work scientists are doing now to identify the threats of new and existing PFAS chemicals should shape the way Hoosiers and their legislators use and regulate them.

“This group of chemicals is starting to grow. But I mean, there's just so much we don't know, whether or not there's information out there in the public, and whether the legislators know much about it or not. I think that's part of the importance of the role, I think what we can do as researchers is just have discussions about what we see,” Freeman said.